By Alex Harasymiw

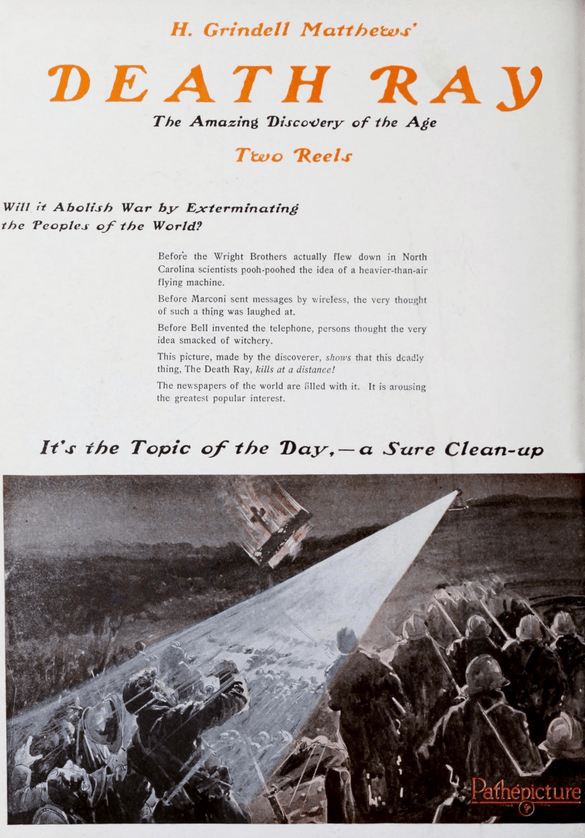

Promotional poster for The Death Ray (1924)

Introduction

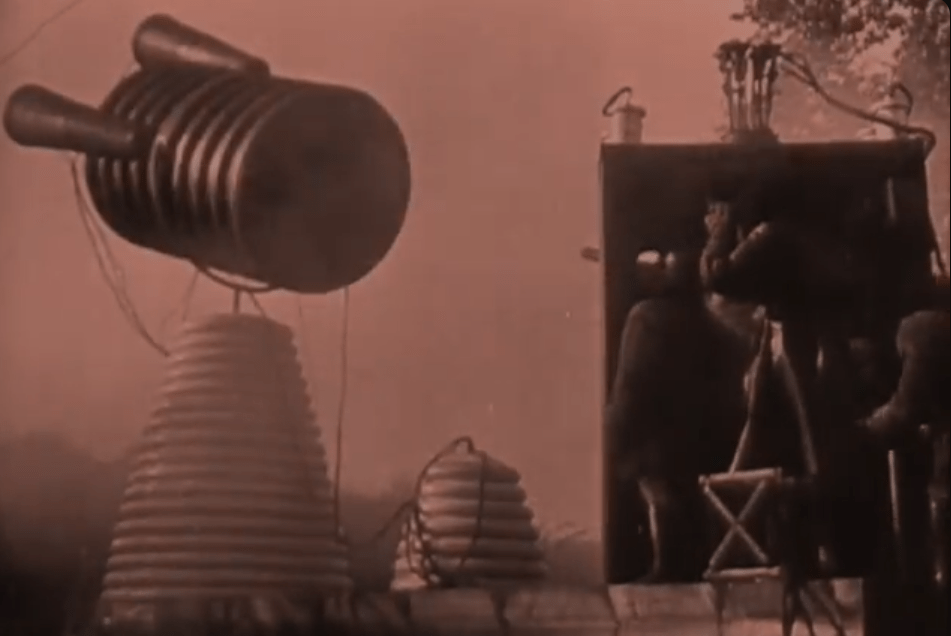

There, squatting beside a bush, projecting from the field, like a tilted spotlight precariously balanced atop a porcelain beehive, we behold the death ray, its tentacle-like power cables snaking across the English countryside to somewhere off-frame. Invented in 1923 during the interwar period as the ultimate deterrent to the enemies of England, Harry Grindell-Matthews’ device sits mercifully unused, mysteriously untested, a mere testament to the destructive potential of the modern scientific mind. From the surviving photographs and the rare newsreel footage of the death ray, we can see an eerily thin beam, sweeping across an assortment of objects, a motorcycle engine, a lump of gunpowder, a quivering mouse, like that of a handheld flashlight, only, instead of illuminating each of the objects, the beam slices them like a pair of scissors, severing them from the sense of continuity between one moment and the next. First, there is light and the object, a rupture, and then an explosion to splice the two parts together. In the end, Grindell-Matthews would destroy the device, along with all the related plans, notes, and records, leaving behind only anecdotes, rumours, and film strips as evidence of this great realization of science fiction in the past.

Apart from its strange imagery, like some untimely precursor to the independent exploitation films that would appear decades later, the death ray is fascinating for the way it lingers in the popular imaginary. Despite the lack of conclusive demonstrations of the device, the way descriptions of it change from one account to another, and Grindell-Matthews’ reticence about its materials and operation, there appears to have been a widespread faith in the real possibility of the invention’s existence, and even today something like a pious agnosticism surrounds the death ray. When we consider the efforts of early silent cinema scholars to confront the often irreparable degeneration or complete loss of the films of so many marginalized filmmakers, and the implications of such loss for our understanding of the history of silent cinema, the persistence of the death ray as the lost work of a modern inventor-genius seems especially questionable. Where the absence of marginalized films and filmmakers from the official canon of silent film history is often attributed to the real material loss of their films in the present, the death ray highlights one of the central ironies of historical writing about this period: namely, that if a narrative is compelling enough to be believed, there is no problem inventing evidence to suit its ends.

Illumination and Destruction

For the archetypal figure of this form of historiography, we need look no further than Harry Grindell-Matthews. According to his faithful biographer, Ernest Barwell, who holds Grindell-Matthews in such high regard as to refer to him in the preface of his biography as the Winston Churchill of science (Barwell 7), it is the total loss of Grindell-Matthews’ inventions that ends up being his most valuable legacy. Barwell credits Grindell-Matthews with an almost prophetic awareness of the threat the then-rising Nazi Germany would pose to Britain in the future, which he claims inspired many of his dubious inventions. The British government never did purchase any of his creations, let alone the fabled death ray. According to Barwell, however, this sense of personal failure as an inventor is overshadowed by the significance of his decision to destroy every trace of his inventions:

That is the tragedy of Grindell Matthews. It is also his triumph. In the closing days of his life, when every man’ hand was against him, and even those who had pledged themselves to remain steadfast had left his side, he rose to far greater heights than when he was front-page news in every newspaper in the world. Anyone can refuse to barter his patriotism when he is wealthy and in good health, but when poor and suffering greatly from heart trouble it is not so easy to refuse a life of ease and comfort. That was G.M.’s achievement, and those who criticized, misunderstood, and under-estimated his genius may well ask themselves whether their patriotism would have stood the strain so well. (Barwell 10)

In an interesting reversal, Grindell-Matthews earns his place in British national history through the absolute secrecy of his inventions. His virtuous poverty and suffering make him seem more akin to our image of the modern artist than that of the scientist; his genius is in leaving nothing behind but the vague menace of his inventions’ capacity for destruction.

M. Grindell Matthews, inventeur du rayon mortel. 1924. Wikimedia

However, in 1924, the menace of the death ray seemed for many as real as its appearance on a projector screen. One editor for Time magazine recorded his impressions of the death ray in the somewhat bathetically titled, “What Use to Write Books, Poems?” After viewing a filmed demonstration of the death ray, privately exhibited for an audience of reporters in Grindell-Matthews’ laboratory, the shaken editor connects this invention to the general state of modern life, in which “Death, whether by death-ray or automobile accident, [is] just as cruel, kind and inevitable as ever—just as inevitable as bad novels and good novels coming in a steady stream across my desk” (Time). The death ray in this context is not a novelty in the modern context, but one more ambiguous development, like the dangers of the modern city, and the uneven quality of modern cultural production. The unusual comparison between death in modernity and the state of the modern novel suggests something of the editor’s effort to restore a sense of narrative cohesion to a life often headed for a meaningless, depersonalized end. Just like the senseless plot developments in a poorly conceived story, the arbitrary nature of a modern death wrecks the effort to reconcile the individual’s psychological development with their destiny in the world. In this sense, the editor’s skepticism seems to center more on the ethical dilemma posed by the death ray. Would the death ray succeed as a deterrent to Britain’s enemies or bring about the destruction of the planet and the end of human civilization? The scientific soundness of the experiment represented in the film, however, is curiously absent from the article. The existence of the death ray seems to be inevitable, even if it is not in fact possible.

Here, it is worth pausing over this effort to not only connect the invention of the death ray to more general observations about the texture of modern life, but also show how it exemplifies a particular aesthetic sensibility. Drawing on the works of Walter Benjamin and Siegfried Kracauer, American silent cinema scholar Ben Singer notes how the developments of modern life in the early twentieth century saw the emergence of a corresponding aesthetic sensibility, that of sensationalism (Singer 91). In both cinema and commercial entertainment in general, the new shocks, ruptures, and perils of modern urban experience demanded a counterpart in cultural production, with “the commercialization of the thrill as a reflection and symptom (as well as an agent or catalyst) of neurological modernity” an almost inevitable consequence (Singer). The Time article above further reflects just such a sensationalist aesthetic. In an effort to relate the destructive potential of the death ray, its invention is somewhat puzzlingly compared to the proliferation of the automobile and the fear of being run down in the street. The pose struck in the article is that of the pompous, self-gratifying indignation of the literati, for whom the death ray becomes a catalyst for both bemoaning the death of high art at the hands of commercial cinema, as well as the lost narrative cohesion in a life where the plodding rumination on great ideals and values can be suddenly cut short by a random distracted motorist. The cinematic nature of the ‘modern’ death was merely thrilling and sensational, unlike in literature, where texts seem to promise that the ultimate fate of individuals is a more or less intelligible consequence of their own way of living. The death ray is at once seen as a logical consequence of modernity, and yet remains utterly, and perhaps deliberately, unintelligible within the narrative framework of the modern novel. The paradoxical fictionality of the death ray thus illuminates a shadowy gap between the anxieties of modern life and the explanatory power of literature, one which calls into question the hegemony of the author the more it commands and empowers the curiosity of the general public.

After being repeatedly spurned by the British government, who refused to purchase his invention, Grindell-Matthews approved the public release of an 8-minute film, Death Ray (1924), which purported to demonstrate the power of his device. Directed by French special effects and trick cinematographer, Gaston Quiribet, much of the film’s runtime is taken up with listing unrelated inventions of modern science, Grindell-Matthews’ credentials as a prototypical inventor-genius, and the media sensation surrounding the death ray. A little over two minutes of the film is devoted to scientific experiments, with the death ray shown illuminating some coiled wire and igniting a pile of gunpowder at a distance. The film’s intertitles do most of the heavy lifting and there is very little sense of continuity due to the frequent cuts. A close-up of the Eiffel Tower’s electrical wires reminds us that “history can repeat itself and the seemingly impossible become a reality” (1:16); shots of newspaper headlines stand in for the inventions of “one of the boldest thinkers of Modern Times” (2:54); the image of Grindell-Matthews as a prophetic scientist-genius reinforced by shots of him sitting pensively behind a desk and flying in an airplane (3:00, 3:54). The experiment itself shows Grindell-Matthews fiddling with some switches, then a cut to a close-up of a glowing wire held between two of his lab assistants (5:07). Grendell-Matthews pulls a lever, and then there is a sudden cut to a close-up, and then an over-the-shoulder shot of the pile of gunpowder igniting (6:34). At the end of the film, even the intertitles appear to confuse the speculative and the concrete with the claim: “The destruction the Death Ray may be able to accomplish with its power to Illuminate or Burn, at great distances, would be unlimited” (7:02). The destructive potential of the death ray remains a possibility, for it “may” have this power, and yet we can still be certain that such power “would be unlimited.”

Still from Gaston Quiribet’s The Death Ray (Pathé, 1924)

Despite its relatively late production in the history of silent cinema, the showmanship of Death Ray shares a number of similarities with films often associated with the ‘cinema of attractions.’ Film scholar Tom Gunning characterizes this period of silent cinema as one that “directly solicits spectator attention, inciting visual curiosity, and supplying pleasure through an exciting spectacle – a unique event, whether fictional or documentary, that is of interest in itself” (Gunning 384). With its emphasis on tricks and novelties rather than narrative, and its efforts to directly address the spectator through sensory and psychological impressions, the cinema of attractions inspires audience participation in its spectacles and thus stimulates a more direct involvement with the medium than the passivity demanded of audiences in theatrical productions or narrative films (385). In this sense, the cinema of attractions does not designate a particular set of images, tricks, or effects, but rather something more like a “primal power” latent within cinema, and moreover one not confined to a given time period (387). Much as Singer emphasizes the neurological impacts cinema simulated in its appeals to the modern spectator, Gunning’s cinema of attractions highlights the way film addresses, and in so doing, actively constructs and shapes, its spectator.

Much as in Gunning’s definition of the cinema of attractions, Death Ray complicates a strict division between spectacle and narrative. Although the film contains a loose narrative arc, building from the early history of wireless communication up to a speculative future in which the death ray dominates the battlefield, the effect of Death Ray on the spectator comes from a sort of simulacral exhibition of scientific rigor and authority. Just as Gunning calls attention to how “[t]he Hollywood advertising policy of enumerating the features of a film, each emblazoned with the command, “See!” shows this primal power of the attraction running beneath the armature of narrative regulation” (387), the splicing of intertitles together with otherwise unrelated fragments of the Eiffel Tower and Grindell-Matthews getting into an airplane likewise evokes the power of the attraction in the service of its narrative. Diagrams and headlines taken from a few newspapers stand in for footage of Grindell-Matthews’ remote control submarine and a radio capable of communicating with airplanes. In this conspiracy of spectacle and narrative, Death Ray mobilizes the indexicality of film to produce the effect of evidence for inventions that do not exist. Here, the figure of the scientist is transformed into that of a showman, with allusions to the positivism of science providing the spectator with the inspiration and illusory sense of continuity necessary to stitch together otherwise disparate fragments into a cohesive whole.

Still from Gaston Quiribet’s The Death Ray (Pathé, 1924)

In a field such as early silent cinema, where so many of the films, personalities, and communities of the historical record are apparently missing, the revelation of a film claiming to possess an abundance of evidence for things that never existed to promote a man of no importance looking to defraud the British government is somewhat farcical. The irony of this situation is especially pronounced after reading Alyson Nadia Field’s introduction to the spring issue of Feminist Media Histories, “Sites of Speculative Encounter,” where she characterizes the early silent cinema studies as a “history of survivors:”

To an overwhelming extent, the field of cinema and media studies has been organized around extant material, with histories closely tethered to surviving evidence. Film history is a history of survivors, written at the expense of alternative voices and practices that risk being dismissed or marginalized if we can’t readily access them. When scholars aim at a broader and more inclusive film history, we often hit a wall. Instead of working with archival abundance we are faced with degrees of archival silence; what survives is often fragmentary at best and deliberately elided or effaced at worst. (Field 3)

For Field, the dependence of film historians on the surviving films from the silent era leads to the construction of historical narratives that at least implicitly exclude alternative perspectives and communities from the imagination of the history of early silent cinema and its canon. Instead, if the historian looks to unearth these forgotten memories, they must grapple with “archival silence” in the form of fragments, omissions, and the destruction of past films. Instances of fragmentation, elision, and obliteration represent obstacles to the historian’s effort to realize alternative narratives as cohesive wholes. The historical irony of the death ray and the survival of the Death Ray newsreel is in how it deliberately fragments an existing archive of stock footage, newspaper articles, and exhibitions to smuggle Grindell-Matthews into a canon predisposed to hero worship and the retrospective celebration of the isolated, misunderstood genius.

The persuasiveness of this fragmentation in Death Ray comes from the effort to reconstruct the spectator as the privileged witness of a scientific process. Again, Ernest Barwell’s 1943 biography of Grindell-Matthews offers some insight into this reimagination of the spectator. Having been trusted with access to the Grindell-Matthews lab at Harewood Place, Barwell recounts the initial death ray experiments:

Further experiments revealed that vermin which had been subjected to tests were killed instantly, and G.M. knew the possibilities of the ray he was seeking to harness. Each of us was pledged to secrecy, and the inventor took the precaution of ordering his apparatus from firms spread all over the country, thus hoping to keep any gossip from developing. But whispers of the things going on behind the walls of Harewood Place reached the ears of the news-gatherers of Fleet Street, who had got into the habit of associating the name of Grindell Matthews with anything which savoured of mystery or magic. (Barwell 91)

Here, the biographer offers his eyewitness testimony of the death ray’s ability to kill, but due to his participation in the conspiracy is unable to provide details about the construction of the device or the origin of its materials. The secrecy surrounding the death ray is justified by speculation as to its potential for destruction, on the one hand, and the presence of enemies waiting to co-opt it, on the other. To the initiated, the experiments are rigorous and methodical, but to those on the outside, they suppose, it can only be experienced as “mystery or magic.” What is especially interesting about the construction of the death ray witness is the way they remain, with respect to the construction of the device, just as much on the outside as the rest of the variously curious or dismissive public. That is, the witness does not actually possess any special knowledge of the death ray, how or whether it works, but merely an initiation into a particular narrative, one which reframes their ignorance as an informed and virtuous ignorance.

Were the death ray of Gaston Quiribet’s Death Ray newsreel confined to the realm of fiction, the effort to unmask the processes involved in persuading the spectator to suspend their disbelief would be a little pedantic. Rather, I argue that what makes Death Ray compelling is the way it illuminates the artifice of historical narratives and canonization. Throughout the newsreel, the primal power of the attraction Gunning associates with the spectacles of early silent cinema is co-opted in the name of positivism and the scientific process. The newsreel stitches together otherwise disparate fragments as evidence of causal relations between an inert device and combustible material. The sense of narrative cohesion in the film comes from the initiation of the spectator into the mystery of the device, an initiation that works not as a revelation of how it operates, but rather a strong desire for it to work. In so doing, the death ray reveals the circular process in which the persuasiveness of a particular historical narrative can invent a death ray, and the invention of a death ray can in turn help construct a particular historical narrative. Here, the death ray appears as both cause and effect of history, with its power over the spectator deriving as much from the evocation of a narrative as from the experience of a spectacle.

In the Hands of the Enemy

Contrary to the wishes of Grindell-Matthews, the death ray would leave Britain’s shores just a year later and arrive, not in Nazi Germany, but in the Soviet Union. When Soviet director and film theorist Lev Kuleshov’s silent science fiction film, The Death Ray (Луч смерти,1925) arrived on the scene, the film was considered ideologically suspect by Soviet film critics. In the realm of fiction, this cheap exploitation film, apparently cashing in on the sensationalism surrounding Grindell-Matthews’ death ray, represented an inexcusable departure from the aesthetic and thematic demands of Socialist Realism (Kovacs 38-9). Kuleshov’s own defense of The Death Ray reflects something of Grindell-Matthews’ own aloofness towards the ethical implications of his death ray, arguing that he had merely been experimenting with the possibility of reproducing the production quality and formal characteristics of American films on a much smaller budget: a pursuit which, he admits, may have distracted him from a more careful consideration of the thematic content of the film (Kovacs 39). For both the inventor and the director, there is an effort to position the death ray outside of history as the logical outcome of formal experimentation. However, while Grindell-Matthews’ death ray is caught up in a cycle of incessant invention and production in its own historical context, the tension between narrative and spectacle in Kuleshov’s Death Ray represents an instance of historical rupture, with the orientation of the collective towards scientific discovery offering the possibility of alternative organizations of the social order.

Lev Kuleshov, The Death Ray (Луч смерти, Goskino, 1925)

Notably, both the first and last reels of Kuleshov’s Death Ray are lost, which invites speculation into the literal framing of the film. The remainder of the film begins with the camera panning across a village littered with the bodies of massacred workers following a failed protest, and then a somewhat non sequitur transition to the actors’ credits. Afterwards, we see the manager of Edith, a world-famous gunslinger played by Soviet actress, Aleksandra Khokhlova, propose to her. She puts off his proposal until a later date, a plotline that is never resolved due perhaps to the loss of the final reel of the film. The rest of the surviving film involves the invention of a death ray and the conflict between two parties, the fascists of some unidentified Western country and the workers of the Soviet Union, who jostle for control over the invention. Much of the action comes in the form of impromptu slapstick spectacles, such as when a woman chases away a gang of fascist spies by throwing a gratuitous number of plates at them (9:00), or in scenes of these same fascists slapping each other around in mutual recognition of their incompetence (17:00). The surviving film ends as an army of workers races to confront a squadron of fascist bombers with their newly acquired death ray, with no apparent resolution.

In terms of both its material and formal composition, the fragmentary Death Ray resists narrative integration into a cohesive whole. Writing on the relationship between spectacle and narrative in “Pie and Chase: Gag, Spectacle, and Narrative in Slapstick Comedy,” Donald Crafton offers the following definition of the revolutionary potential of gags in the slapstick genre:

One way to look at narrative is to see it as a system for providing the spectator with sufficient knowledge to make causal links between represented events. According to this view, the gag’s status as an irreconcilable difference becomes clear. Its purpose is to misdirect the viewer’s attention, to obfuscate the linearity of cause-effect relations. Gags provide the opposite of epistemological comprehension by the spectator. They are atemporal bursts of violence and/or hedonism that are as ephemeral and as gratifying as the sight of someone’s pie-smitten face. (Crafton 363)

According to Crafton, the power of the gag lies in its ability to not only destabilize narrative frameworks, but also to frustrate the spectator’s ability to apprehend the narrative in a film as such. The spectacle of a gag, as much within the film as at the expense of its narrative, offers the spectator a sense of pleasure in the experience of the illegibility of the film. In this way, the narrative fragmentation within a slapstick film works to disrupt the meaning-making process of narrativization, and instead reorients the spectator towards the radical energy animating the growth of digressions at the expense of ostensibly causal relations.

Throughout Kuleshov’s Death Ray, this tension between spectacle and narrative plays out in the slapstick treatment of the invention itself. Just like Grindell-Matthews’ Death Ray, Kuleshov’s film contains a scene exhibiting the power of the death ray in a laboratory setting. The editing in the fictional exhibition of the death ray almost perfectly mirrors that of the Grindell-Matthews experiment, with first a group of scientists crowded around a glowing apparatus, followed by a sudden cut to a beaker exploding (18:00). Not long after this demonstration, fascist goons break into the lab and attempt to steal the device. After one of the fascists trips over an electrical cord and starts a fire in the lab, a protracted fight scene ensues, with the goons running around the house, accidentally shooting each other, and engaging in a prolonged shootout with the scientists in the dark, after which they eventually manage to steal the device (23:30-26:00). This at times bumbling, at times sinister contest for control of the device complicates the representation of the death ray in the Grindell-Matthews experiments. Where the spectacle of these experiments becomes bound up with a narrative of the ambiguous celebration of the aloof scientist-hero as a historical agent and the impotence of the modern spectator, spectacle in Kuleshov’s Death Ray disrupts the device’s narrative function, distracting from its allegorical potential or sensationalized aestheticization. Just as the death ray in this scene remains shrouded in darkness, illuminated only by the momentary muzzle flashes from the gunshots, the rest of Kuleshov’s Death Ray represents the device as a mere prop in a protracted and often farcical contest between competing historical agents. The spectacle of their competition, replete with elements from the slapstick genre, emphasizes the ambivalence of the formation and contestation of historical discourses, the violence and comedy of this process, at the expense of a celebration of a single, cohesive narrative construct.

The material fragmentation of the film further draws attention to the process of narrativization itself at the expense of cohesion. At the climatic moment of the film, a team of workers speeds along a country road, rushing to intercept a squadron of fascist bombers, with the death ray balanced precariously on the roof of their car and a mob of villagers trailing in their wake. One of the protagonists, Engineer Podobed, shouts above the crowd, “Comrades, victory is in our hands! Let’s restore order!” and is immediately set upon by the jostling mob, whereupon the film cuts off, the final reel lost to time (1:15:35-1:15:55). This new ending illuminates the central irony of the death ray throughout the film: namely that as much as it is taken to be an instrument for determining the course of history, once it is firmly in the hands of one party, it ceases to have any power. As soon as the death ray is poised to make some decisive intervention in the plot, apart from breaking hapless beakers in a laboratory, the film comes to an end without resolution. In this sense, the fragmentation of Kuleshov’s Death Ray proves to be itself a dramatic spectacle at the expense of narrative cohesion, where even the promise of narrative resolution offered by the device of the death ray results in the material destruction of the film itself.

Conclusion

The death ray has a long and varied history within the science fiction imagination. It is certainly beyond the scope of this brief article to fully capture the significance of death ray imagery across the genre e. What I hope to have demonstrated with this article are some of the ways in which the death ray illuminates the relationship between filmmaking, archival loss, and the historiography of early silent cinema. In the case of Grindell-Matthews, the conjecture surrounding the invention of a death ray moves from the realm of speculative fiction to historical necessity as the anomalous byproduct of modern hero worship and canonization. For Kuleshov and what remains of his film, the death ray not only destabilizes historical narratives but, once activated, seems to destroy the very materiality of the text that served as fodder for these competing ideological constructions of reality. Historically speaking, the death ray is almost by design the object of conspiracy and espionage with an apocalyptic potential that we ignore at our peril and to our detriment. Who knows what discursive powers the death ray might unleash for the maniacal historian or film scholar? I say, we need only look to the past for a taste of how the world might yet be remade.

Bibliography

Barwell, Ernest Haydn Garnet. The Death Ray Man. Hutchinson & co., ltd., 1943.

Berlant, Lauren, Sianne Ngai, Alenka Zupančič. “Sustaining Alternative Worlds: On

Comedy and the Politics of Representation.” Texte zur Kunst, no. 121, 2021, pp.

64-85.

Crafton, Donald. “Pie and Chase: Gag, Spectacle and Narrative in Slapstick Comedy.”

The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, Amsterdam University Press, 2006, pp. 355-365.

Field, Alyson Nadia. “Sites of Speculative Encounter.” Feminist Media Histories 8.2,

2022, 1-13.

Gunning, Tom. “The Cinema of Attraction[s]: Early Film, its Spectator and the Avant-

Garde.” The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded, Amsterdam UP, 2006, 381-388.

Kovacs, Steven. “Kuleshov’s Aesthetics.” Film Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 3, 1976, pp. 34–

40, https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.1976.29.3.04a00070.

Singer, Ben. “Modernity, Hyperstimulus, and the Rise of Popular Sensationalism.”

Cinema and the Invention of Modern Life, University of California Press, 2020, pp. 72–100, https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520916425-005.

The Death Ray (Луч смерти). Directed by Lev Kuleshov, Goskino, 1925.

The Death Ray. Directed by Gaston Quiribet, Pathé, 1924. https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=qbNgvHfK4wI.

Vago, Mike. “This inventor’s death ray was totally real, but no one was allowed to see

it.” AV Club, 25 August 2019, https://www.avclub.com/this-inventor-s-death-ray-was-

totally-real-but-no-one-1837447697. Accessed 19 January 2026.

“What Use to Write Books, Poems?” Time, 25 Aug.1924, https://web.archive.org/web/

20101121074507/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,846539,00.html. Accessed 19 January 2026.

~

Alex Harasymiw is a PhD candidate in the Department of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature at the University of Minnesota. His research focuses on representations of climate collapse and apocalyptic discourse in Chinese science fiction films and literature. He is also interested in speculative historiography and Soviet science fiction.

i don't wanna keep secrets just to keep you

Feb. 22nd, 2026 07:30 pmI then baked some oatmeal for breakfast for the week, and made macaroni salad for a few days of lunch, and then for dinner, I made angel hair as planned, though when I actually read the recipe, it was not anything new to me - it was what I always do for a super quick tomato sauce, except they were adding chile crisp to it, which I guess is the thing nowadays - every recipe I read has chile crisp in it, but I'm not really a chile crisp person. I have the heat tolerance (in terms of spiciness, though I also don't like my food super hot temperature-wise either) of the whitest baby you know.

Anyway! It is a super easy but delicious meal and if you don't mind waiting a few extra minutes, you can do it all in one pot. Boil your pasta - angel hair is best for this, imo - and reserve a cup of pasta water before you drain it. Return the pot to the stove over low heat and add in a nice glug of olive oil (2 tbsp if you need a measurement), and then add a whole can or tube of tomato paste to the oil (so between 4 and 6 oz). Stir it around and season it as you like - I used garlic and onion powder, oregano and red pepper flakes and salt, but if you want to get fancy, you could probably saute a diced shallot and some minced garlic in the oil for a minute or two before adding the tomato paste - for 2-3 minutes, until it's all hot and sizzling. If you are so inclined, add chile crisp to suit your taste. Then add the pasta back, and about half the reserved water and toss it until the pasta is coated. I only used 4 oz of angel hair, so if you have more, you might need more water. Then put it in bowls and sprinkle it with parmesan cheese. If you are in an even bigger rush, you can sizzle the tomato paste in a frying pan while the pasta cooks and then combine it all back in the pasta pot. The couple of minutes you save isn't worth having to wash an extra pot to me, but it might be to some people.

*

Weekly proof of life: recent media | Spring Crunch Eve

Feb. 22nd, 2026 03:10 pmI also read a few more volumes each of Hikaru no Go and The Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service, but I'm still in rereading territory with both. (I think I've already read up to vol. 12 of Kurosagi, but for Hikaru, I think the odds are against me really realizing when I've hit new territory until I go to enter a volume in Goodreads and find it's not already on my Read list there.)

Watching:

With my crunch time at work starting, it's not an ideal time for us to start a show that's a significant time commitment or that's going to leave me desperate to see a next episode when work is eating most or all of my evenings. It's possible this will result in me just showing

(I still don't feel actively fannish about HR at all, but am enjoying being adjacent to it and seeing all the fannish excitement and meta and such. I have saved many fic recs to my read-later list on A03, but have yet to actually read a single one [and may never, given how slowly I go through fic--there's still a steady stream of Guardian fic I haven't read that also goes on that list].)

Weathering/Working: We have what sounds like a significant nor'easter blizzard arriving at some point tomorrow, with heavy wet snow. Will this be where our luck fails for the season and we lose power for the first time? (I'm completely astonished that it hasn't happened yet. Probably it's not really because the generator and backup power are warding that off, like carrying an umbrella around...)

And of course the spring crunch is set to start tomorrow in the late afternoon, right around when the storm is likely to be in full swing. Will the weather have much impact? (Mainly, I guess, in terms of Those Who Speak all being able to make it there safely; I kinda hope that there's some kind of backup power in their actual building, but I don't know for sure one way or the other.)

it would be so fine to see your face at my door

Feb. 21st, 2026 09:15 pmI also made dressing for coleslaw, which I've never done before - always just bought the pre-made deli version - and it's ok, not great. Not tangy enough, tbh. I wonder if replacing some of the mayo with buttermilk is the way to go. I ate some with a steak I pan-fried for dinner and that was nice. I don't have steak very often, but sometimes it goes on sale and I get it.

We're supposed to be getting between 12"-18" of snow tomorrow/Monday (wait, I just checked, and the current forecast is 39% likelihood of at least 18" if not more, wow), and I'm supposed to go into the office on Tuesday, so I guess we'll see what actually materializes, whether the streets are cleaned, and how I feel on Tuesday morning. Supposedly we're getting a free lunch, but I don't know when the consultant who is supposed to be buying it for our in person meeting is flying in, idk what is going to happen. There was some back and forth on Teams today about the storm and they are notifying everyone to be remote on Monday, which is the smart choice.

Anyway, my menu is not very cozy - I was planning on making that lemony macaroni salad for lunches, and some baked oatmeal with cherries and chocolate chips for breakfast. I do have bread, milk, and eggs, so there could always be French toast! Though I did make that on Wednesday when I realized it was Ash Wednesday (and that I'd completely forgotten Shrove Tuesday). I'll probably have pasta for dinner tomorrow regardless, since it's Sunday.

Today, I watched Batman Ninja, which features the Batfamily time traveling back to feudal Japan (but so much Joker and I am so tired of Joker), and then its sequel, Batman vs. the Yakuza League, which I enjoyed more because it has Wonder Woman in it and she's fantastic as always. It also features ( I guess this is a spoiler ) It was weird to me though that we got 4 Batboys (Jason's feudal Japan headgear is HILARIOUS), but no Cass or Babs at all, and I didn't love the art for Selina. Someday we'll get an animated version of Wayne Family Adventures and the girls and Duke will get their due!

*

My motor cortex learning to play Dark Souls

Feb. 21st, 2026 09:07 am(Except that these guys mastered jumping WAY faster than I did.)

It's hilarious and delightful to me to watch people having an experience of Dark Souls which is not wholly unlike mine. In a weird way I feel kind of #represented.

In later vids, they have (like me) discovered the joys of the halberd as adaptive technology for people who are bad at spacing and aiming.

Supernatural vid: Life is a Highway (the 20th anniversary vidding project)

Feb. 20th, 2026 11:45 pmAnyway ... I first started making fanvids for fun in 2002, but I began posting them on LJ in 2006, and since 2026 is therefore my 20th anniversary of posting the first one (#what) and I've been wanting to get more of them on AO3, I decided to make that a project for this year!

So here's my 2006 one and only Supernatural vid, Life is a Highway.

This isn't the first one I put online, but of the 2006 vids I think it's probably one of my favorites and a good one to start with. Contains clips up to late season one because that's all I'd watched at that point and most of what was available. Here's the original LJ-imported-to-DW post. Please enjoy this dive into

Some notes if you'd rather read them afterwards

Obviously at this point all I have is the exported file rather than the original vidding files (as this was at least 5 computers ago) so 2006 quality is what you're getting, including some slight wonkiness with jerky video and slightly odd cropping (I was screencapturing the video, which explains both the slight borders that occasionally appear - I got a lot better at cropping later - and a few instances of jerkiness as my 2006 computer struggled to render the video). The credits also include my original 2000s-era LJ name, which some of you may remember.IIRC, I was making these earliest vids on a really old copy of Adobe Premiere that I had absconded with from my college computer lab in the 1990s.

Also posted on AO3.

If you want a 12 Mb download in 2006 quality, you can download it here!

Also, an interesting bit of context on the 20th anniversary vidding project - I discovered recently that I uploaded a bunch (most? all?) of my older vids to Vimeo in 2016 on the private setting, so apparently I was planning a *10th* anniversary vidding project, but got derailed somehow. What is time.

Wuthering Heights Review

Feb. 20th, 2026 11:59 pm- it’s a 2 hour long music video: glib, flamboyant & silly.

- the child actors were GREAT. Bless them. Cracking work, really sad that the story scooted forward to the adult actors so fast.

- I love Margot Robbie & I mean no disrespect when I say ( Read more... )

me and my big mouth

Feb. 20th, 2026 05:07 pmUh, so, I have a weird Jew-y dilemna.

I volunteer with my neighborhood "snow brigade", which shovels for folks who need help. We're due to get some gross "wintry mix" and "icy sleet" overnight, although maybe not much accumulation.

The couple I got assigned to emailed to say — well, here: "Hopefully there will be NO snow on Friday night and Saturday since for religious reasons we are not able to shovel. If it's not much we can deal with it Saturday night."

I emailed back to say that I don't consider helping a neighbor in need to violate shomer Shabbat and I would be happy to come by and make sure their sidewalks and steps are clear.

They said, "It would be our sin to have another Jew do any work for us on Shabbos. We very much appreciate your kind thoughts to help us. But if we can't do it, you can't do it for us either."

Uhhhhhhhhhh. I am not sure how to respond to this. I don't think this is a sin! I try to observe Shabbat in the sense of resting and renewing myself, but very much not in a traditional way — like, spending a couple of hours mending and embroidering might be part of Shabbat for me because it fills my cup and I don't always get the chance to during the week! Going to the farmer's market and spending half my paycheck and cooking something elaborate on Saturday is a profoundly Shabbosdik thing for me! I don't want to tell them "your theology is wrong" and I don't want to upset them by doing something they have told me not to do (and would apparently feel guilty about????), but ... I can't just leave an elderly couple trapped in their house with icy sidewalks for a day!

*pinches bridge of nose*

I gotta get in touch with the snow brigade coordinator and tell her what's going on so she can try to find a substitute, I guess. I wish I hadn't made it so obvious I am also Jewish, just said something cheerful about being happy to shovel in the morning, but it truly did not occur to me that their observance would mean this. My bad. Ugh.

This is gonna be a real fun conversation with the snow brigade coordinator.

ETA: Snow brigade coordinator is going to check if there's someone I can swap with for future Saturdays, but since the blizzard has been delayed until Monday, when labor is allowed, we will deal with it if and when it becomes a problem next. What a ridiculous shenanigan.

(no subject)

Feb. 19th, 2026 09:31 pmI seem to be Canadian now, which is very exciting. (My paternal grandfather was born in Ontario.) I need to pull together a relatively short stack of documents to prove it (3 birth certificates, 2 marriage certificates, 2 name change records), and fingers crossed Canada (home and native laaaaaand) will welcome me home.

It is supposed to snow AGAIN this weekend. I keep reminding myself that this is how winter is supposed to be.

My to-do list has three MUST DOs on it:

- write up notes for therapist before Monday session

- read & comment on manuscript for crit group Tuesday

- pollinator garden email

If you see me doing anything else except, like, keeping body and soul together for the next few days (if it snows more than half an inch, I'll have to take care of my neighbors, and a friend is coming over with her kid to encourage me to clean and have dinner, but other than that — !), yell at me until I go back to my aforementioned tasks.

I spent this week in slide deck hell and the week before in spreadsheet hell. There is still more slide deck hell to come, but I think I can pace it out a little more now. But spreadsheet hell will not end until May, thanks to HHS (pdf link). I like accessibility work, but I also like digital paleography and information architecture and wireframing and right now accessibility is expanding to fill all the available time and then some. Fortunately, one of the slide decks from hell actually requires me to work on a writing project, so I can cling to some vestige of being a creative person who doesn't live in slide deck or speadsheet hell. Maybe someday I will actually be one! Maybe someday I can contribute to CanLit!

the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat

Feb. 19th, 2026 05:25 pmHilary Knight with the game-tying goal with 2 minutes left and the goalie pulled - she became the all time leading US scorer at the Olympics! GOATed! (She also got engaged yeserday{? I think it was yesterday? to a lady speed-skater} so she's having a time in Milan!) And then Megan Keller won it in OT - right through the 5-hole on Desbiens (who I do feel bad for - she had herself a game today after getting pulled in the previous US-Canada game)! What a sick goal!

(I don't think the overtime in a GOLD MEDAL GAME should be 3-on-3, but at least they were scheduled to play a full period - no shootout in the gold medal game.)

Of course, I was supposed to be working so people kept emailing me and calling me and I couldn't be like, "Don't you know the US women's hockey team is in OT against Canada in the gold medal game!??!" so ugh. work.

In other news, last night I was struck with a mighty strong craving for an Orange Julius, and i had an unopened 11 oz bottle of OJ in the fridge so I stuck it in the freezer, and then this morning I pulled out the blender to make it, and I think the part that defrosted enough to get scraped into the blender was all water, because it had only the vaguest of orangey taste. But I have the other half of the bottle left, so I will try again tomorrow. I'm sure nostalgia is playing a part, but there was something so amazingly good about an Orange Julius at the mall when I was in high school.

*